27 Sep Cuba: 1929-2019

In 1929, James Abbe travelled from Paris to Havana to write an article for the London Magazine about American influence on the island.

It was during Prohibition in the States, and the clubs and casinos of Cuba were full of Americans escaping the confines of the liquor ban. What Abbe found was that American investment in Cuba, and their profits, extended far beyond the tourist trade.

In 2019, 90 years after his visit, Abbe’s granddaughter great-grandson, along with an associate of the James Abbe Archive, now return to Cuba, bringing along a portfolio of images from Abbe’s journey, in advance of the 500th Anniversary of the City of Havana.

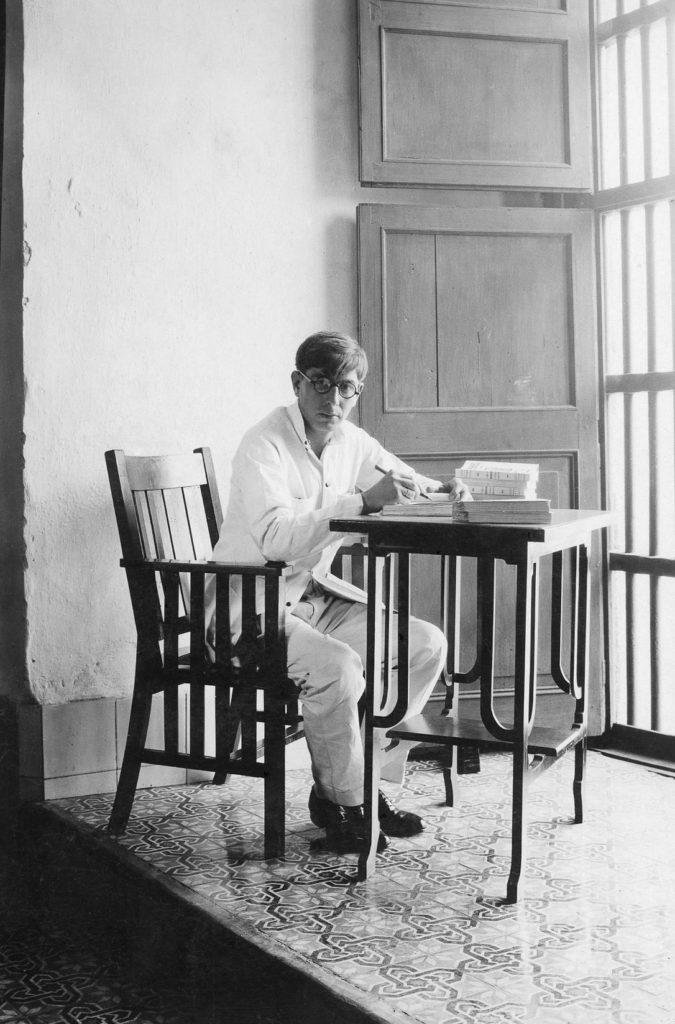

Abbe’s images and observations highlight the unrestrained dominance of American influence and development during that era. But, they also reveal much about those who lacked privilege—notably his portraits of inmates at Principe Prison. He feigned envy of one illustrious prisoner, Carlos Montenegro, who parlayed his confinement into writing popular novels. Abbe wrote: “This author accomplished, in a unique manner, that which all of us who try to write dream of. He killed a man who annoyed him, and for the past nine years has been able to write undisturbed and without the mental handicap of having to pack up and leave the next morning.”

Montenegro’s book, Hombres sin Mujer (Men without Women), a testimony of life in the prison, has been called one of the most important Cuban novels of the first half of the 20th Century.

Cuban author Carlos Montenegro signs copies of his novel from a patio in Principé Prison, Havana, 1929 © James Abbe Archive 2019

Abbe’s stay in Cuba was cut short by rebel attacks in Mexico, where Abbe couldn’t resist going to cover the conflict. At the end of his last column from Havana, he inserted: “STOP PRESS.—Tramp Photographer and adjutant departed for Mexican revolution. Inform next-of-kin.”

The Escobar Rebellion was one of the last regional wars to break out following the Mexican Revolution. Abbe met two other reporters on the ground—the only three members of the press to witness the Battle of Jimenez. His “adjutant,” or assistant, had been left in Brownsville Texas awaiting a visa and plane fare, and missed all the action, joining Abbe later in Mexico City. Abbe’s description of the deprivations in the desert, including a lack of food and water amid constant deadly assaults, were graphic; some of his images, gruesome.

Following the battle, he traveled to Mexico City to see a friend he’d met in Russia, artist Diego Rivera, and then was allowed to take refuge in an old monastery, courtesy of George Enciso, the head of Mexico’s Department of Belles Artes. Some churches had been made available to artists and art schools as a result of anti-religion laws put in place during the Revolution. Abbe and his assistant stayed in one of these chapels, using it as their staging ground for days spent capturing images and stories.

Abbe was so captivated by the people and lifestyle of Mexico that in a dispatch to London Magazine he said he’d sent for his family, to stay. Instead, he returned to Europe, where his instinct to follow the action led to expansive coverage of the brutal lead-up to World War II.

Similar to Abbe’s 1934 book about photographing in Russia, his travels to Cuba and Mexico reveal an understanding of two complex and culturally rich nations otherwise prone to stereotypes and misrepresentation in the English-language press.

Click here to view a gallery of James Abbe’s photographs from Cuba.

Learn more about the Abbe Archive’s trip to Cuba by clicking here.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.